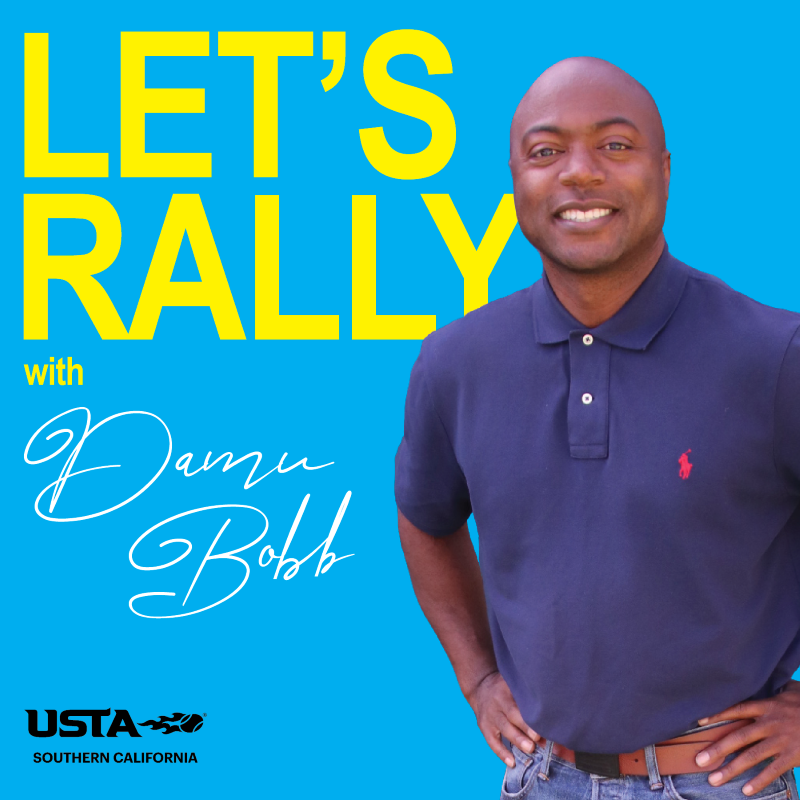

Damu Bobb is a man who wears many hats. He lives and breathes sports media as an Emmy-winning professional, plays the role of tennis dad on SoCal sidelines, and feels just as comfortable in a pair of Jordans as he does in Kenneth Coles – though he admits his special occasion footwear is the Nike Sb Air Trainer 1 “Chlorophyll,” a.k.a. the John McEnroe.

A member of the USTA SoCal Board of Directors and DEI Committee, Bobb brings a voice of experience to the table. He recently spent some time to share his thoughts on creating opportunities in DEI, the next Serena Williams, the best advice he received as a youngster, and that elusive pair of collaborative kicks still on his radar.

Q: In many ways the last two years are a blur, but it’s easy to recollect the emergence of Black Lives Matter and the often-volatile conversations that followed. Months later, the Asian community dealt with misguided hate. One thing that has resulted from these moments is the discussion around Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at work, in schools, and even on the tennis court. In your eyes, how has the tennis community responded to the concepts of DEI, and what lies ahead in terms of forwarding the DEI movement in the sport?

A: Looking back further than the last two years, tennis in the United States has historically been a sport for the upperclass white community. Similar to golf, it has been a sport of wealth, country clubs and exclusivity. For years, in many places where tennis is played, Black people weren’t even allowed entry, let alone to play. We’ve made tremendous progress since those dark days. To me, DEI just means justice. As a new member of the (USTA SoCal) Board, I’m excited that the board is committed to justice and fairness in our sport not only on the players’ side of the court, but in the business management of US tennis, too. Our goal is to give diverse and underserved communities access to the same kind of facilities, coaching and resources that others enjoy so that they can experience and enjoy the lifelong benefits of the sport.

Questions that involve leadership and governance are those most often associated with growing DEI in tennis – what we can do at the higher levels. But for the average weekend player, who realizes the racial inequities at their clubs or in tournaments, how do those people take steps to make a positive impact on diversity and equity?

Diversity and equality are important in sports, as they allow players to see each other and acknowledge their differences. However, country clubs can be their own little private communities and have historically excluded or been unwelcoming to minorities. I can remember playing junior tournaments in the deep South and feeling the stares and sometimes overt racism, being called names and being subject to unsportsmanlike conduct. What bothered me most is that other players and families witnessed what was happening and didn’t say anything. No one was being held to account. The communities and players at the club level have to hold each other accountable to stamp out the kind of behavior that comes from within their own communities. “Anti-racism” signage on the courts and in the clubs, as they use in the English Premier League, is a useful reminder to all players and fans that the responsibility is ours to be better.

It’s fair to say that the next Jerry Rice will get a shot at playing football somewhere. It’s fair to say the next Usain Bolt will get a shot at track somewhere. Can we be confident that the next Serena will be afforded the opportunities to grow and excel in tennis?

Honestly, the era of American dominance in tennis is wavering. So, we have a lot of work to do make sure that our system can continue to produce the world’s best tennis players. Part of that commitment is making sure that we recognize and develop the talent of players of all races and ethnicities. The American talent pool runs deep, we just need to make sure everyone gets a chance. The world only knows Serena because her father, Richard Williams, fought through tremendous obstacles in our own developmental system that made it difficult for her because she was Black and not rich. She was successful despite our system, not because of it. I’m excited by the tremendous progress we’ve made over the last two decades. But we can only be confident of another Serena if we are committed to a system that is fair and recognizes talent wherever it may be and whatever color body it comes in.

Frances Tiafoe has said, paraphrased, if you let your racquet do the talking, you don’t need to be talking yourself. In a TMZ world that lives and breathes on social media, is it enough to let the racquet talk?

Author Ashe once said, “Athletes, especially black athletes, must use every resource at their command to right things that are wrong….To have a potential to do a lot of good and not exercise this is the worst cowardice, especially in the United States.” The benefit of being in a “TMZ world” and being a high-profile athlete is that you have an opportunity to use your social media and people will listen due to your relevance. Pro athletes have about 4-5 years in which they are relevant, and they should take advantage of that. Young people that look like Frances want to hear from him, hear his story, know how he practices and how he thinks. Through social media, Frances is a real-life template for young people to follow and emulate.

In our current world, we have players standing up for Ukraine, standing up for COVID vaccinations, or standing up for equal pay on the tennis tour. Take for example, Venus Williams, who has fought for equal pay for women in the tennis world. Or Naomi Osaka, who wore a BLM mask as she walked onto the court, taking a powerful stance to continue the conversation so that victims of police brutality are not forgotten. Or Elina Svitolina, who has used her platform to spread calls for peace in her native Ukraine. All these players let rackets talk, but by using their relevance they are pushing a conversation that could lead to change.

So, Frances Tiafoe is correct that your racquet can speak for you on the courts, but off the courts, as a high-profile athlete, they can also use their voice to stand up for the various social issues which I believe is a great opportunity.

Let’s lighten things up a bit. In your Twitter bio, you refer to yourself as a sneakerhead. Does this mean we’ll find you camped out on any given Saturday morning at dawn on Melrose Avenue?

I definitely would call myself a sneakerhead, but I’m a little too old to camp out on Melrose Avenue. My love for sneakers came when I was 12 years old when I got sponsored by K-Swiss as a junior tennis player. I received free K-Swiss Si-18 International sneakers every month, which made me a popular kid at school. My parents were in heaven, as I would go through a pair of sneakers in a week during the summer season on tennis hard courts. The great thing about tennis shoes, like basketball shoes, is that you can wear them off the court and be stylish. I have a decent collection of Air Jordan I’s. I’m still trying to get my hands on the Air Jordan | Roger Federer collaboration- Zoom Vapor Tour AJ3 ‘Black White.’ When Roger wore those at the US Open a few years back, I screamed, “I need those!”

You’re also a tennis dad. Best tennis advice that you learned as a youngster that you passed on to your own kid(s)?

My uncle Ron (Dr. Ron Grant) would always say, “What you do in practice is what you do in the game. So, always try your hardest in practice.” He had a little rhyme with it. “Good, better, best. Never let it rest until your good becomes better and your better becomes the best.” I am constantly telling this to my kids when they are playing tennis, soccer, basketball, and even in their schoolwork. There are so many life lessons you can learn from tennis and sports in general, but I truly enjoyed practice and getting better at the sport. My advice to any young player would be to take practice seriously and enjoy the process of improving on this journey.

This feature first appeared in “Net/Game,” the official publication of USTA Southern California.